I’d like to begin by thanking Mia Simon for inviting me to talk with you this morning. I’m glad to be here. There are a number of familiar faces in the room and I’m happy to be back among them. My periodic returns to CUNY are almost always opportunities to recall how many interesting things I got to do and how many wonderful people I got to work with. As you have heard, John Mogulescu and I worked side-by-side for about thirty years and I think we were good partners, both of us inspired by rage at what we hated and both of us unwilling to let what had always been done determine the limits of what we wanted to do. I have known many of the people involved with CUNY START—Mia, Gayle, Hilary, Steve Hinds—for many years and have had the good fortune of learning a great deal from them–about reading, writing, math–but also about passion and determination.

Having acknowledged how many people I know who are part of the CUNY START project, I now want to provide a disclaimer. I know a fair amount of the history of the project and I know something of the current state of affairs but I do not have anything like deep or fine-grained knowledge of the rewards and challenges of CUNY START as you experience them day after day. And I certainly am not going to try to tell you what you should be doing. I do hope that what I have to say will be of some value as you go forward.

I plan on covering a few things:

- the general state of remediation at CUNY and across the United States;

- the need for a fundamental systems reorganization and some ideas about what such a systems reorganization might be built from;

- some ways in which CUNY START is a pioneer in such a systems reorganization and some thoughts about how the CUNY START community might sustain and preserve itself (for information about CUNY START, go to: http://www.cuny.edu/academics/programs/notable/CATA/cti-cunystart.html.

But first, I’d like to read part of a story. If some of you have heard me tell it before, I ask your patience. I do find that each time I read it, I notice something else. The story is from an essay by Michael Cole and Peg Griffin that was originally published in 1986. The original text is not available online but a link to another version of it is included on the list on the sheet of paper you’ll be receiving shortly. Please humor me and leave the sheet (see handout at end) with the print side down for a few minutes.

This is a story about a girl named Deanna, who was in fifth grade. She was having trouble in becoming a good reader and was participating in a university-based experimental program intended to help kids get better at reading. On one occasion, during a pre-testing session, Deanna and the other children involved were asked to read a three-paragraph story, which had been adapted from a newspaper article, and then answer a ten question quiz. They were told that they could ask the teachers and tutors for help. Ms. G. was one of the teachers and she had previously worked with Deanna. Now the story:

Deanna read the three-paragraph story, evidently with little trouble; at least, she looked at the paper for some period of time and she did not request assistance. The story was about a 10-year-old in a nearby community who was in a coma after having hung himself while trying to demonstrate to a friend what he had seen on TV. …. As Deanna read it, no one observed any special reaction. She turned to the quiz. For the first twp questions, the only help she wanted was some help with handwriting, but she formulated the answers herself.

The first question asked about what had happened to the boy victim, Jared Stockham. She answered that he had accidentally hung himself. This was an adequate answer, as was her answer to the second question,

Then she asked Ms. G. for help with the third question. She claimed it was unfair. The question asked who Eric Burton was. He was the child who had been playing with the victim and who told the adults what had happened. Deanna insisted that the question was unfair. When Ms. G. failed to understand how she could help or what was unfair, Deanna pointed out that the name Eric Burton appeared three times and that you couldn’t answer that kind of question. Ms. G. could not understand what was wrong with the name appearing three times or how that related to the question being a kind of question that could not be answered.

Ms. G. was still in the dark about the unfairness, but started to read the paragraph in question with Deanna. The conversation that followed was a collaborative, two-party act of reading, with the teacher asking questions that reading the sentences would help Deanna to answer, and helping Deanna figure out some words, to paraphrase some ideas, and to make up questions and answers about some connections among the phrases and sentences.

After a few minutes, and unexpectedly, Deanna became quite agitated. She exclaimed in surprise, asking, “He hung himself?”

Recall that Deanna had provided, as an answer to the first question, exactly what she was now asking for verification about. Now, several minutes later, it was new information, worthy of exclamation, question, comment and emotion.

Deanna had a way to answer reading test questions, but it had very little to do with comprehending what she had read. “Word barkers” is a phrase used to describe people who can read words without knowing what they mean. Deanna’s performance suggests that more than words can be barked, and that the barking can be in writing as well as through oral language. Her “answer” to the first question and the “unfairness” of the third question reveal a part of what reading instruction has given her as a way to understand reading. We call it copy matching, and we find more children than Deanna doing it.

Under the copy-match analysis of reading, the question about Eric is unfair because the use of the name three times leaves this kind of reader without a unique thing to copy for the answer. The question about Jared can be answered by taking the phrase next to his name in the opening paragraph and making a copy match in the answer slot on the quiz paper. Deanna has a quite sophisticated copy-match reading procedure: She transforms nouns into pronouns and adjusts verb tense and aspect appropriately, but otherwise gives a verbatim copy of the text in her answer, including spelling and punctuation marks.

Interpersonally, in synthesis with the adult, Deanna can substitute the adult analysis of reading (that includes synthesis of abstract representations of sounds into words and comprehension of whole stories) for her analysis of reading as copy matching. Unless special care is taken to engineer the interactions, this “passing” … goes unnoticed.

The authors went on to suggest that what might be considered traditional instructional approaches with Deanna would, all but inevitably, result in Deanna getting better and better at doing what might be considered “not really reading” and her continuing to be perceived as a not very good reader—while, in fact, she was not a reader at all. Lest you think this kind of thing is unique to reading, let me ask you now to turn over the sheet of paper in front of you and look for a minute at the five addition problems—with the wrong answers produced by the same student. Is there a method to the answers? [A member of the audience responded that the student had added all of the digits.] I assume we all would agree that no teacher ever taught him to do addition in this way but he came up with it anyway. Would more traditional math instruction do much to alter this student’s diligent application of his own rule?

I have a very different personal example to illustrate the possible bad effects of practicing less than effective strategies. When I was ten or so, I taught myself how to swim in the Sunset Park pool in Brooklyn—but I taught myself very bad swimming. If I would practice what I learned then, I would become better and better at being a bad swimmer. I probably wouldn’t drown but I wouldn’t get very far either. What I need to do is to unlearn bad swimming! My children and grandchildren are awaiting the day when I start.

Let me now review some of the stark realities of the state of remediation in American education. I don’t especially want to dwell on the number of students who are placed into remedial courses when they enter college—other than to emphasize that how well colleges respond to their needs makes a big difference in the educational futures of millions of students. Currently, close to seven million students are enrolled in community colleges and approximately 60% of them are determined to need remediation in at least one area. It is a separate question whether or not all of those determinations are appropriate. More about that below! In any case, though, it means that perhaps as many as four million community college students have either taken or could be taking a remedial course and that doesn’t count students placed into remediation at four year institutions. And what do we know about the efficacy of remedial courses? Tom Bailey of the Community College Research Center reports that less than 30% of community college students placed in a remedial course complete the prescribed sequence. In almost every case, that means they will not graduate. And, in fact, the graduation rates for students needing remediation are extraordinarily low. At CUNY, the six-year graduation rates for students who enrolled in associate degree programs in the fall of 2001 were: 15.7% for those with three remedial placements; 21.1% for those with two, and 24.4% for those with one. At the risk of belaboring the point, it is clear that colleges have not become very good at doing remediation.

Much, of course, is made about the extent to which the public schools, in this city and elsewhere, are not adequately preparing students for college. Interestingly enough, at the beginning of open admissions at CUNY more than forty years ago, it was commonly believed that remediation would be a short-lived necessity because, once it became known how inadequately prepared many students were, the city’s schools would raise their standards and improve their instruction. Clearly, that has not occurred. But I’d like to suggest that the reason why the schools have not become terribly more effective at producing graduates ready for college is pretty much the same reason why the colleges have not become terribly more effective at remediation. What we have is a recurring and self-reinforcing pattern of students who are not being successful in what might be considered the satisfactory development of literacy and math knowledge and skills at various points in elementary school, middle school, high school and college being provided remedial instruction that rarely makes much of a difference but that, often enough, enables students to squeeze by to the next grade or level, only for them to be ensnared again and sent off to repeat the process. Of course, many of them don’t repeat the process because they simply disconnect and then drop out—occasionally from middle school, at a rate of about 30% from high school and at a rate above 70% from community college. I think it’s fair to say that the basic features of traditional remedial, as well as non-remedial, instruction look much the same in middle school, high school, adult literacy and GED programs, as well as college developmental programs. So while what I’m talking about today is focused on the college level, I believe it is equally applicable to the schools that enroll younger students.

So what does traditional instruction look like? Norton Grubb, of the Graduate School of Education of the University of California/Berkeley, has been publishing findings based on research he and his colleagues have been conducting on instructional practices in basic skills classes in California community colleges. His tentative conclusions are quite distressing, although not necessarily surprising:

The vast majority of instruction follows the practices of remedial pedagogy, which involves drills and practices on small sub-skills (subject-verb agreement, grammar rules, sentence-level writing, converting fractions to decimals or solving standard rate-time-distance problems) that most students have been taught many times before, in de-contextualized ways that fail to clarify to students the reason for or the importance of these sub-skills. This has been called part-to-whole instruction, emphasizing the small parts or sub-skills that presumably are assembled into a whole, which refers to broad competencies like the comprehension of varied texts, understanding of mathematical procedures and thinking, and the ability to write in several genres. In remedial pedagogy, these larger competencies rarely are practiced or experienced in any way, so instruction results at best in students mastering small sub-skills.

The full impact of that negative assessment, however, is only realized in the context of Grubb’s description of what might be considered optimal instruction. Based on a review of research on learning (documented by the National Academy of Sciences in publications such as How People Learn and How Children Learn), Grubb has argued for the appropriateness of a “high-quality balanced” approach. Balance refers to a balance between what might be understood as the best of behaviorist and constructivist models of learning—providing extensive opportunities for students to figure things out for themselves and, at the same time, providing expert assistance about the power of the effective use of rules and formulas. But balance is not enough; quality matters as well. Grubb writes:

Some dimensions of instructional quality are common to all pedagogical approaches; content mastery; warm and supportive relationships with students; explicitness about the purposes of instruction; clarity in presentation; care in providing the prerequisites for understanding before developing new material; developing checks for student understanding; and using student errors to diagnose how students are thinking (sometimes incorrectly) about a topic. Other dimensions of quality are specific to particular approaches. For behaviorist teaching, the techniques of direct instruction suggest a careful progression of introducing a new topic, presenting it to students, having students practice with guidance (or “scaffolding”), and finally having students work independently.

Grubb suggested that remedial pedagogy is characterized by a lack of balance (and a definite tilt towards the behaviorist end of the spectrum) and low quality—in other words, the worst of all possible worlds.

In an overview of research into “promising” models in developmental education in 2010, Elizabeth Zachry and Emily Schneider of MDRC suggested that those promising models had not been nearly as effective as many of their promoters had hoped: They wrote:

Virtually all of the programs that have been experimentally evaluated using random assignment methodology have shown either no increases in academic success or only modest increases in student persistence or credits earned rather than long-term effects on student over-all achievement.

I’m quite critical of random assignment methods. I cite the researchers who rely on them only because, in the past, those same methods have often been used to promote one or another of the various promising models that now appear to have accomplished so little. And furthermore, they wrote:

…. a number of researchers and policymakers have begun to suggest that developmental education in its current form is broken, and have called for a more radical re-envisioning of these programs. Noting that more conventional efforts to improve students’ achievement have produced only modest results, these individuals have sought to restructure the core curricula of developmental education programs and offer more innovative ways to help students build their skills. While still new and untested, these ideas offer a fresh perspective for advancing academically underprepared students’ success, which may hold some promise for more radical improvements in these students’ achievement.

Uri Treisman, of the Dana Center at the University of Texas and a principal architect of the Statway initiative at the Carnegie Foundation (as well as a graduate of Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn and the son of a mother who still lives on Ocean Parkway), has argued that “developmental education in mathematics needs to be wholly redesigned, rather than revised around the edges.” Indeed, Treisman has suggested that efforts to improve remediation were like “building a six-lane highway into a swamp”—because of the startlingly low rates of success in college-level math classes. Treisman’s comment suggests that more than remediation needs to be overhauled.

But what might a pedagogical systems reorganization look like? I want to recommend that we consider the wisdom of moving from remediation towards re-mediation (as you can see on the handout, there’s a difference—at least in the spelling). You might think that this is little more than a linguistic quibble but I want to encourage you to think that it’s much more consequential than that. In the first instance, remediation is derived from a medical sensibility that imagines the individual has an illness of sorts that needs to be remedied. In the second instance, re-mediation is derived from a school of thought which sees human development and learning as deeply grounded in a complex set of mediations—among people, including teachers and learners, and things, especially tools, including intellectual tools like language, literacy and symbolic manipulations. Mediations are perhaps best understood as interactions. In other words, inter-personal relations come before and shape intra-personal learning. Learning is not only, and maybe not even primarily, in the head. In that second case, the analysis suggests that individuals who have not been successful in learning have been deprived of supportive and conducive learning environments. Worse still, they have often enough been in far too many environments that were fundamentally hostile to the possibility of learning. At times, those responsible simply haven’t cared; but far more often I believe they didn’t quite realize the adverse effects of what they were doing—they were following what I would describe as a commonsensical approach in designing remedial courses. Kris Gutierrez of the University of Colorado has described such courses:

…. courses in which (students) develop unproductive and weak strategies for literacy learning. In general, their literacy instruction is organized around individually accomplished tasks, with generic or minimal assistance, narrow forms of assessment, ‘homogeneous’ grouping, and an over-emphasis on basic skills with little connection to content or the practices of literacy—in short, on the technical dimensions of literacy.

Gutierrez goes further:

Instead of emphasizing basic skills—problems of the individual—“re-mediation” involves

re-organizing the entire ecology for learning, and “a shift in the way that mediating devices regulate coordination with the environment.” Development here involves a “systems reorganization” in which designing for deep learning requires a “social systems reorganization” where multiple forms of mediation are in play. The concept of re-mediation constitutes a framework for the development of rich learning ecologies in which all students can expand their repertoires of practice through the conscious and strategic use of a range of theoretical and material tools.

Gutierrez approvingly cites the work from more than two decades ago of Glynda Hull and Mike Rose, who called for a reconsideration of the concept and practices of remediation in writing. They “proposed a social-cognitive approach that employed fine-grained analysis, process tracing, retrospective interviews, and observation of students’ writing … to help document a student’s writing history. With methods that help make visible a logic in students’ writing, they argued, instructors can develop new understandings of students’ writing, their potential, and the appropriate pedagogical intervention.”

The work of Hull and Rose, as well as many other outstanding writing educators, was fundamentally grounded in the work of a not very well known CUNY path-breaker–Mina Shaughnessy. In the very early days of Open Admissions at CUNY, Mina took seriously the intellectual challenge of figuring out what to do with students who had arrived at City College all but completely unprepared for college-level work and whose writing often seemed to be a strange tangle of words and punctuation marks—often enough, teachers had no idea where to begin. Eventually, Shaughnessy uncovered and promoted the wisdom of taking seriously the actual writing that students produced and investigating the inner logic of their “errors.” In 1976, she published a seminal text, Errors and Expectations, a book that is still worth reading more than thirty years later. She read thousands of student essays in an effort to understand what they were doing—just like Ms. G. tried to understand what Deanna was doing and just like you did a short while ago when you tried to understand what that young math student was up to. Beyond pointing out the value of understanding students’ strategies, she also embraced the power of their motivations. She wrote:

The term “basic writing” implies that there is a place to begin learning to write, a foundation from which the many special forms and styles of writing rise, and that a college student must control certain skills that are common to all writing before he takes on the special demands of a biology or literature or engineering class. I am not certain this is so. Some students learn how to write in strange ways. I recall one student who knew something about hospitals because she had worked as a nurse’s aide. She decided, long before her sentences were under control, to do a paper on female diseases. In some way this led her to the history of medicine and then to Egypt, where she ended up reading about embalming – which became the subject of a long paper she entitled “Post-mortem Care in Ancient Egypt.” The paper may not have satisfied a professor of medical history, but it produced more improvement in the student’s writing than any assignments I could have devised.

Tragically, Mina Shaughnessy died an early death in 1977 and the promise of her work was never really realized at this University. The recently deceased poet, Adrienne Rich, was one of the people Shaughnessy attracted to teaching writing at City College. At a memorial service after Shaughnessy’s death, Rich recalled what Shaughnessy had taught her colleagues about teaching:

By personal example, Mina taught many of us that teaching is not charisma, or inspiration, but careful preparation and hard work. That impressionistic and histrionic methods were a waste of a student’s time, that a romantic pedagogy cannot take the place of a truly accurate identification. She managed to convey all of this without preaching or admonishing, by the kinds of examples she brought to staff meetings, by her own presence which became, for me at least, a kind of personified intellectual conscience, and, above all, by her respect, untinged by white liberal romanticism, for the minds of the young women and men with whom we were working.

I hope that what I have said thus far hints at what is so special and so important about CUNY START. While the origins of the reading/writing and math curricula used at CUNY START share some fundamental common convictions with the researchers and thinkers I’ve mentioned, they have their own rich and distinctive characteristics. I believe it is likely, in the years to come, that people will look back to the work of the individuals who developed and taught in CUNY START with the same kind of appreciation that people have for the work of Mina Shaughnessy, Glynda Hull and Mike Rose.

Let me emphasize that continuing to do what has been being done in remedial courses for forty and more years is irresponsible. But change is hard to come by. Uri Treisman has observed that:

The mix of faculty autonomy and highly dispersed incentive and authority structures constitutes an almost perfect immunological system that enables higher education to reject efforts, political or educational, to change its core practices. Higher education is effectively organized to protect academic freedom, but, as Ewell (2002) has observed, its organizational features also “act to subvert change of any kind.”

I also want to acknowledge how hard it is to escape the gravity of common sense. Some of you may have read the recent New York Times op-ed by Judith Clayton-Scott of the Community College Research Center on the adverse effects of universal placement testing. I thought she made a pretty good case for the likelihood that individuals were being placed in remedial courses all but completely unnecessarily. But whether she did or not make that case, the really depressing thing was reading the comments responding to her post. It was one whine after another, and I don’t mean the wine you drink with dinner. I’ve included the link to her article and the comments in the resources list. You can judge for yourself.

It is essential that the work and the accomplishments of CUNY START be carefully documented so that they might serve as an inspiration and a potential model for other effors within CUNY and elsewhere. Some of what I see as distinctive about CUNY START are the following:

- a deep conviction about the intellectual capacities of students;

- a willingness to design program structures (including things like the number of hours per week for different purposes and the length of cycles) based on instructional goals;

- deeply coherent and consistent courses of study;

- thoughtful planning and preparation for instruction;

- rich curricular resources;

- a realistic sense of how much time it takes to get certain things done;

- extensive embedded opportunities for new teachers to learn how to teach within the program;

- a determination to scrutinize its results.

Let me turn now, very tentatively, to what I think might be some things for the CUNY START community to consider as elements of a plan for sustainability. I will have not a word to say about the financial aspect. I am instead interested in the social/cultural preservation and enhancement of the project. The things I would recommend paying attention to are the following:

- deep and strong personal and professional supports for staff so that difficult work does not become exhausting work;

- the development of traditions that are embedded in a distinctive programmatic culture and that are supportive of productive routines;

- the need to be explicit with each other and with students—taking meanings for granted almost always produces problems;

- good stories/not anecdotes—keep Deanna in mind (there’s a world of difference between saying, “I can’t believe she didn’t know the kid hung himself” and recreating the rather complex moment that produced Deanna’s confusion and revealed her mind at work);

- close tracking of patterns of student participation and performance—the program should always be alert to evidenced that students in one or more groups are not doing as well as others; every discrepancy in achievement should be reason to reconsider what is being done;

- well established and clearly understood decision-making processes—so that issues of concern to staff members can be brought forward and resolved without disrupting the effective operation of the program.

Let me end with a reaffirmation of why I think CUNY START is so important. In the United States (and truth be known, most other places on the planet), we accumulate wealth and poverty in grossly disproportionate measures; similarly (and, in this instance, we may out-perform other countries), we accumulate educational success and failure in comparably disproportionate measures. Every day that educational failure accumulates, the commonsensical wisdom that we are doing as best as can be expected—given what we know about the troubled lives and dysfunctional circumstances of many students—becomes ever more the conventional wisdom. Far less than many, I do not think that education can alter the profound impact of material realities on what students do. But I also think that what educators do can make a profound impact on what students might do. You are on the front lines of the educational future—please stay there! Many years ago, Mina Shaughnessy, speaking about writing teachers, wrote the following:

For unless he can assume that his students are capable of learning what he has learned, and what he now teaches, the teacher is not likely to turn to himself as a possible source of his students’ failures. He will slip, rather, into the facile explanations of student failure that have long protected teachers from their own mistakes and inadequacies.

But once he grants students the intelligence and will they need to master what is being taught, the teacher begins to look at students’ difficulties in a more fruitful way: he begins to search in what students write and say for clues to their reasoning and their purposes, and in what he does for gaps and misjudgments. He begins teaching anew …

I hope that the wisdom of an old pioneer is helpful to you new ones.

CUNY START (April 30, 2012)

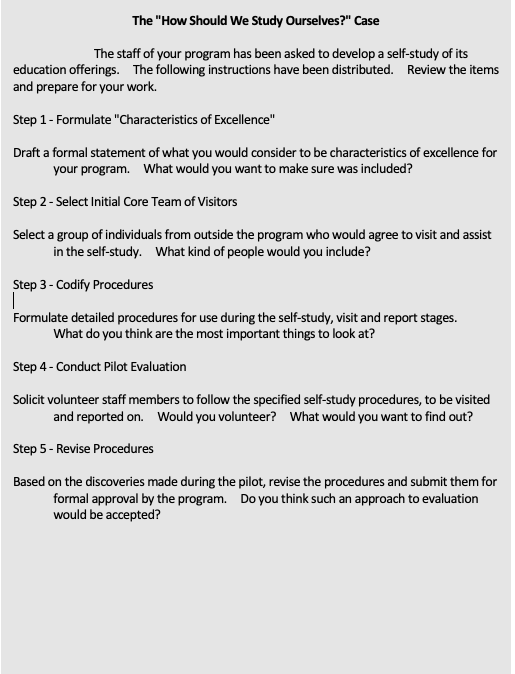

How did he get the answers?

33 1091 8 28 90

+99 + 60 +34 +70 + 6

24 17 15 17 15

What’s the difference between remediation and re-mediation?

Resources:

Tom Bailey:

http://www.postsecondaryresearch.org/conference/PDF/NCPR_Panel1_Bailey%20Jeong%20Cho.pdf

Michael Cole and Peg Griffin:

http://lchc.ucsd.edu/People/MCole/ColeGriffinRemediation.pdf

Kris Gutierrez:

Norton Grubb:

http://www.postsecondaryresearch.org/conference/PDF/NCPR_Panel4_GrubbPaper.pdf

Uri Treisman:

http://www.postsecondaryresearch.org/conference/PDF/NCPR_Panel4_CullinaneTreismanPaper_Statway.pdf

Elizabeth Zachry and Emily Schneider:

http://www.postsecondaryresearch.org/conference/PDF/NCPR_Panel%203_ZachrySchneiderPaper.pdf

Leave a Reply